Second Sunday of Advent

This week's lectionary readings include Isaiah 11:1-10 and Matthew 3:1-12 as we celebrate Peace Sunday.

Prayers for Advent Peace Candle Lighting

O Prince of Peace, bring your really loud peace, your really noisy peace. Create in us the piercing sound of swords becoming plowshares, spears becoming pruning hooks. Pound the steel of our war instruments into truly useful tools. We seek peace that originates and radiates from deep within the stillness of you. Bring your peace and we will genuinely thank you. Amen. (based on Isaiah 2:4)

Peace Sunday

Isaiah 11:1-10 is heard on the Second Sunday of Advent when we typically light the Peace Candle. It would be appropriate then to highlight the extraordinary images of peace and wholeness in verses 6–10. The particular way peace is portrayed in this passage is somewhat unique in the Hebrew Scriptures. People are not depicted as working together in harmony; instead, animals are described as living peacefully. Animals.

Of course, the Christian tradition is rich with allegorical interpretations that view animals as people or nations. For example, John Calvin notes,

Though Isaiah says that the wild and the tame beasts will live in harmony, that the blessing of God may be clearly and fully manifested, yet he chiefly means what I have said, that the people of Christ will have no disposition to do injury, no fierceness or cruelty. They were formerly like lions or leopards, but will now be like sheep or lambs; for they will had laid aside every cruel and brutish disposition.

(John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, trans. William Pringle (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1953), 1:384.)

However, humans are present in the text in that a young boy leads the animals. Either as allegory or not, the imagery is undeniably compelling as a vision of a peaceable kingdom.

Edward Hicks, a Quaker, painted several interpretations of this passage in the nineteenth century, highlighting its tranquil nature. In fact, his influence on recent interpretations of this passage is extensive. Note the painting directly below and the relationships among animals and between animals and humans.

Thomas Troeger has written a contemporary hymn text based Isaiah 11 entitled “Lions and Oxen Will Feed in the Hay.” The hymn includes the following first stanza:

Lions and oxen will feed in the hay,

Leopards will join with the lambs as they play,

Wolves will be pastured with cows in the glade—

Blood will not darken the earth that God made.

Little child whose bed is straw,

Take new lodgings in my heart.

Bring the dream Isaiah saw:

Life redeemed from fang and claw.”

(Thomas H. Troeger, “Lions and Oxen Will Feed in the Hay,” in New Hymns for the Life of the Church: To Make Our Prayer and Music One (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 58.)

It would also be profitable to extend the discussion of peace back to verses 1–5 and the things that make for peace, chief among them, justice. Brueggemann is adamant about the need to place these two sections of the passage in relationship: “I suggest that the new scenario for ‘nature’ is made possible by the reordering of human relationships in verses 1–5. The distortion of human relationships is at the root of all distortions in creation.” (Isaiah 1–39, 102.) The peaceable kingdom is possible only with the implementation of justice by a spirit-filled ruler. Thus, the passage provides Advent hope for a better, more peaceful world while also describing one way to accomplish such a vision.

John the Baptizer and Matthew 3:1–12

Isaiah 11 is not alluded to in the New Testament. However, there is a similar dendrological image used by John the Baptizer in Matthew 3. Thus, the Revised Common Lectionary puts these two readings together during Advent. Despite this pairing, Matthew 3 quotes from a different section of Isaiah (40:3). It would be profitable to read Isaiah 40 instead of Isaiah 11 alongside Matthew 3.

In Matthew 3, John preached repentance, and the religious leaders responded to his call. However, John called them a “brood of vipers” and commanded them to bear fruit, proclaiming, “Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire” (verse 10, New Revised Standard Version). The imagery is somewhat similar to that of Isaiah 11, yet important distinctions are necessary. John called his fellow Jews not to rely solely on religious heritage (“We have Abraham as our ancestor”) but to live faithful lives. The ax and fire then became symbols of the threat of punishment for those “trees” who do not bear fruit. Fruitless trees were otiose in John’s eyes.

When interpreting Matthew 3 today, Christians must be careful not to portray first-century Jews as evil people in need of repentance. John’s label for the Pharisees and Sadducees does not consider their sincerity of faith; the Gospel of Matthew uses these Jewish leaders as opponents of Jesus’s ministry, opposition that is already foreshadowed in their interactions with John. In contrast to Matthew 3, in Isaiah 11, Jesse’s tree has already become a stump; judgment has fallen already, so the oracle sings a more hopeful tune about the possibility of new growth.

Tree of Jesse

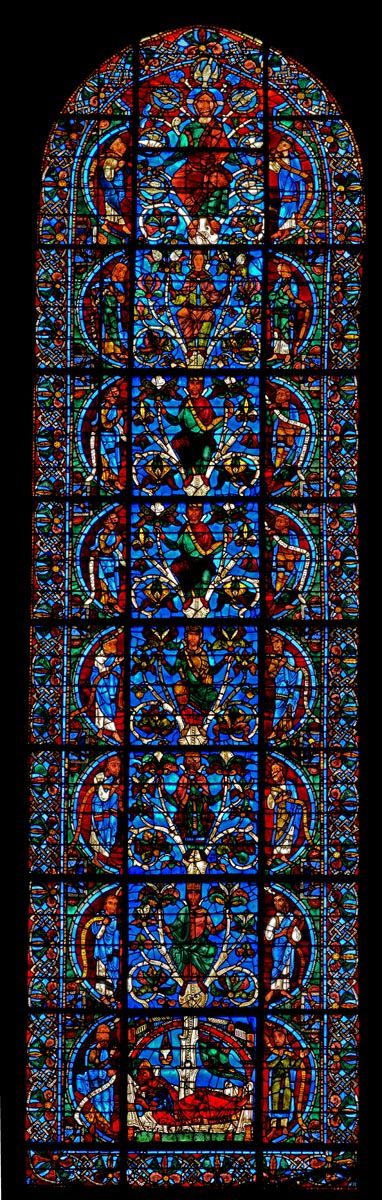

During the eleventh century CE, medieval Europe provided several artistic interpretations of Isaiah 11 in the form of the Jesse tree. The most well-known is probably the Chartres Cathedral window, which dates to the middle of the twelfth century CE. At the bottom of this window, Jesse, the father of David, is depicted as sleeping. A beautiful tree emerges from his side, holding a series of kings, then the Virgin Mary, and finally Christ at the top. Prophetic figures such as Isaiah, Moses, Samuel, and Ezekiel fill out the picture, although they are not directly connected to the main tree branch growing from Jesse to Jesus. The Chartres tree is one of many Jesse trees with the depictions becoming more elaborate over time, and incorporating other figures such as the evangelists and angels.

John F. A. Sawyer (The Fifth Gospel: Isaiah in the History of Christianity(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 77–79) argues the popularity of the Jesse tree in medieval art is related to the cult of the Virgin Mary and medieval society’s interest in royal lineage. Indeed, Mary serves in this artwork as the rod (remember, in Latin virgais “rod” and virgo is “virgin”) from the stump of Jesse.

The art also serves another crucial theological purpose: to demonstrate Jesus’s continuity with, or perhaps better, his fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. The tree grows naturally and inevitably from Jesse through the Davidic kings to Jesus, the Davidic Messiah of Christianity. The tree then does not allow for other branches to lead to other leaders. Continuity and linearity are critical in order to demonstrate the straight line from Jesse (really, David) to Jesus. It is a stylized tree with only one branch, and it may not then be able to provide contemporary Christians with the robust theological imagination we need to explore alternative ways of thinking about prophecy. The vital message of Isaiah 11 is not the accurate prophecy of direct (literal and historical) lineage down through the ages from Jesse to Jesus.

A Benediction (Or Miscellaneous Thoughts)

- If you know someone who might like to read this newsletter, forward this email to them.

2. You can read an online version of this newsletter here.

Member discussion